This article is part of the Criminal Information System Management series, cybercriminal strategic positionning section.

Key Takeaways

- The traditional APT/cybercrime distinction, while operationally useful, obscures the fundamental reality that criminal innovation operates according to organizational principles rather than criminological categories.

- Several comprehensive bibliometric analyses of Open Innovation research covering thousands of papers from 2003-2024 do not identify any studies applying the framework to criminal contexts or discussing Open Innovation Limitation in adversarial settings.

- Criminal organizations can choose optimal innovation modes for specific needs: voluntary collaboration for complex joint operations, appropriative innovation for rapid capability acquisition, and hierarchical support for resource-intensive development.

- Criminal organizations exhibit all characteristics of mature innovation ecosystems, including systematic knowledge integration, professional network structures, and sustained collaborative relationships that transcend traditional organizational boundaries.

1. Introduction

Criminal organizations operating in digital environments display organizational structures that often mirror legitimate business enterprises with a key highligth : innovations within cybercrime represent the cutting edge of global criminal activity (tfcs). The emergence of Crime-as-a-Service models, collaborative malware development, and distributed criminal networks suggests that traditional criminological frameworks may be insufficient for understanding modern cybercrime (prosegur).

While Henry Chesbrough’s Open Innovation framework has been extensively applied to legitimate business contexts since its introduction in 2003, its potential application to criminal organizations has received minimal scholarly attention (hbsp). The intersection of innovation theory and criminal behavior represents an underexplored frontier in academic research. Several comprehensive bibliometric analyses of Open Innovation research covering thousands of papers from 2003-2023 do not identify any studies applying the framework to criminal contexts (roms, roms2, jim, ejim). This analysis addresses this critical gap by conducting an examination of how Open Innovation principles manifest in cybercriminal organizations.

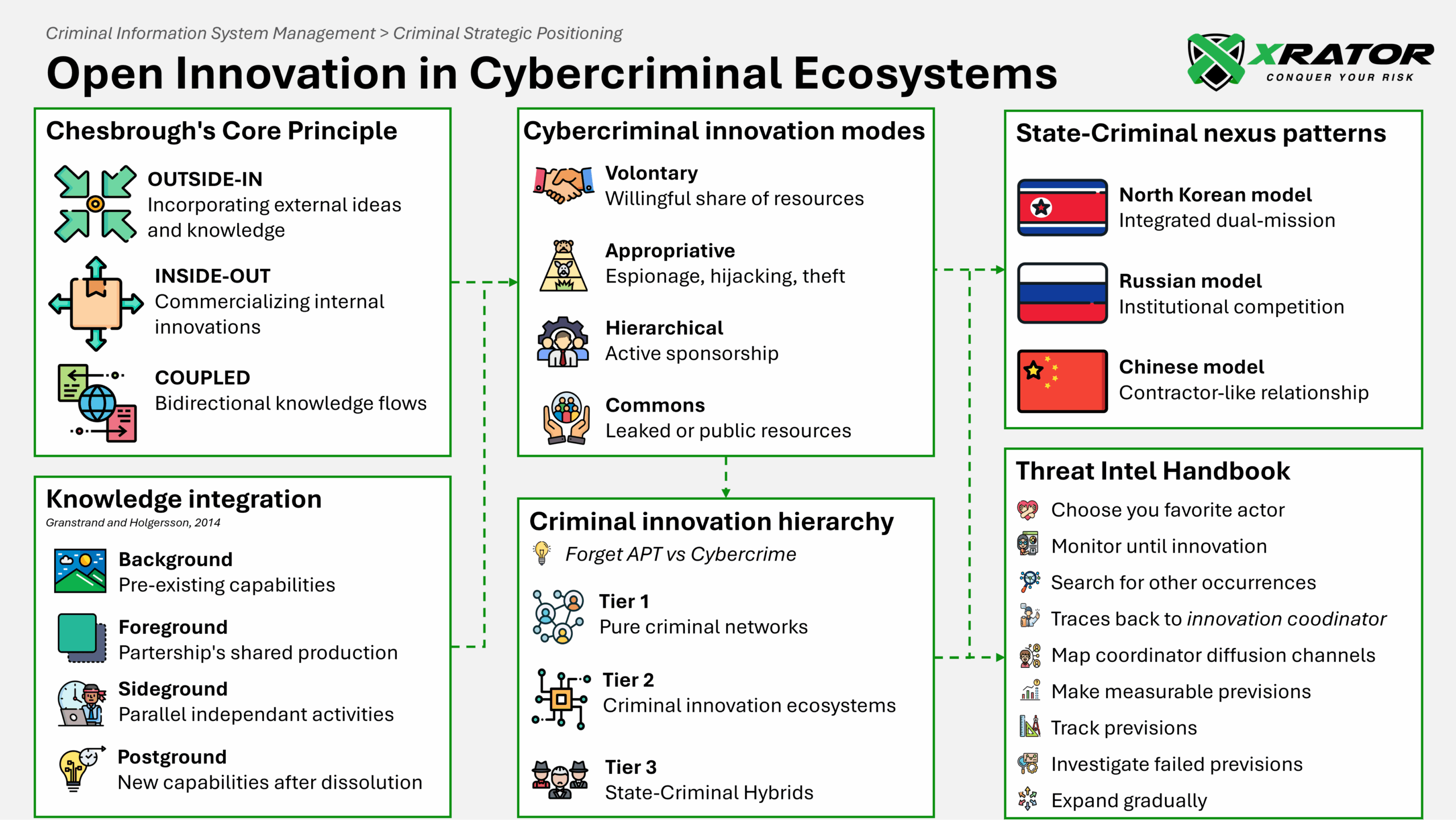

This research examines whether Chesbrough’s three core Open Innovation processes – outside-in (inbound), inside-out (outbound), and coupled (bidirectional) knowledge flows can explain criminal organizational behavior. The analysis synthesizes evidence from academic journals, government threat assessments, and threat intelligence sources to evaluate both the applicability and limitations of Open Innovation theory in criminal contexts.

2. Theoretical Synthesis

Open Innovation has become a central component of the broader innovation management field. The publication of The Oxford Handbook of Open Innovation (2024) marks the maturation of Open Innovation as an academic discipline (oup). Chesbrough’s framework has evolved from organizational-level analysis to multi-level frameworks incorporating individual cognitive processes, inter-organizational dynamics, and institutional influences (ejim).

However, a critical theoretical gap exists regarding illicit organizational contexts. The comprehensive literature review reveals no peer-reviewed studies examining Open Innovation applications to criminal organizations. This absence likely reflects ethical constraints, access limitations, and methodological complexities rather than lack of theoretical relevance.

2.1 Core Open Innovation principles

Chesbrough’s foundational definition of Open Innovation as “a distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms” (oup2). The three primary modes emerge:

- Outside-in Process: Incorporating external ideas and knowledge through technology scouting, partnerships, and crowdsourcing.

- Inside-out Process: Commercializing internal innovations through out-licensing, spin-offs, and joint ventures.

- Coupled Process: Bidirectional knowledge flows combining inbound and outbound activities through strategic alliances and innovation ecosystems.

The criminal context introduces unique constraints that extend traditional Open Innovation theory. The three primary modes then manifest distinctly:

Outside-in Criminal Open Innovation in criminal contexts involves systematic integration of external knowledge through recruitment of skilled individuals, acquisition of tools and techniques from other criminal groups, and appropriation of legitimate technologies for criminal purposes. The Conti ransomware operation exemplifies this through its sophisticated affiliate program structure, where affiliates receive 70-80% of ransom payments in exchange for bringing external capabilities to the organization (bleebingcomputer, cyberdefensemag).

Inside-out Criminal Open Innovation occurs when criminal organizations commercialize their innovations through Crime-as-a-Service (CaaS) platforms, sharing tools and techniques with other criminal actors. The Zeus botnet source code leak created unprecedented opportunities for outbound innovation, spawning derivatives like SpyEye, Ice IX, and Carberp (that itself leaked to give Carbanak) that democratized sophisticated banking malware capabilities (ctc).

Coupled Criminal Open Innovation represents the most sophisticated form, where criminal organizations simultaneously engage in inbound and outbound knowledge flows. The Operation Blockbuster analysis reveals how the Lazarus Group developed centralized malware capabilities while distributing tools across multiple campaigns, creating feedback loops that improved their overall innovation capacity (securelist).

Open Innovation’s emphasis on knowledge flows across organizational boundaries parallels criminal networks’ need to access diverse technical capabilities while maintaining operational security.

2.2 Four-type knowledge integration in criminal networks

The knowledge integration typology developed by Granstrand and Holgersson (2014) provides the most applicable framework for understanding criminal innovation processes (rtm). Their four-type model directly addresses the temporal and ownership complexities inherent in criminal collaboration.

Background Knowledge encompasses pre-existing technical skills, methodologies, and organizational capabilities that actors bring to collaborative ventures.

The Turla group’s sophisticated infrastructure hijacking capabilities, including their ability to scan for and compromise Iranian APT34 web shells across 35+ countries, represents advanced background knowledge accumulated over years of operations (ncsc).

Foreground Knowledge consists of jointly developed resources, shared information, and collaborative innovations produced within partnerships.

The comprehensive malware families identified in Operation Blockbuster (including Destover, Wild Positron, and Hangman) demonstrate systematic foreground knowledge creation with consistent technical signatures across multiple campaigns (securelist, talos, novetta).

Sideground Knowledge captures the parallel activities that members conduct independently while participating in group operations.

The Conti ransomware leak revealed how affiliates simultaneously conducted individual attacks while contributing to the broader organizational mission, creating knowledge spreads that enhanced overall group capabilities (bleepingcomputer, mimecast).

Postground Knowledge represents the most strategically valuable category: capabilities that actors develop after organizational dissolution or partnership termination.

The Zeus botnet source code leak exemplifies this phenomenon, where knowledge initially developed within specific criminal partnerships became the foundation for an entire ecosystem of derivative malware families (kaspersky, thehackernews).

The knowledge integration typology developed by Granstrand and Holgersson provides a solid framework for understanding criminal innovation processes. Their four-type model directly addresses the temporal and ownership complexities inherent in criminal collaboration by categorizing knowledge flows across organizational boundaries and time periods.

3. Transposition Analysis

The most significant theoretical challenge in applying Open Innovation to criminal contexts involves the absence of formal legal frameworks for collaboration. Cybercriminal organizations demonstrate four distinct innovation modes that extend beyond traditional Open Innovation frameworks.

3.1 Theoretical boundaries and limitations

Traditional Open Innovation theory assumes the availability of contract mechanisms, intellectual property protection, and legal recourse for partnership violations (jie). Criminal organizations must develop alternative governance mechanisms based on reputation systems, threat of sanctions, and trust-building through demonstrated reliability.

In criminal networks, trust mechanisms operate through leveraging social capital, emitting signals that are cheap to emit but costly to fake (e.g.: cryptographic signature), and using threat of violent sanctions. Built-in reputation systems, closed instant messaging plateform and chat forums create structured environments for trust development despite anonymity requirements (globalcrime).

Compartmentalization enables knowledge sharing while maintaining operational security through need-to-know information distribution, separate teams for different operational aspects, and controlled modification processes to prevent vulnerabilities.

A Hybrid Governance emerges that combines hierarchical coordination through formal authority structures or figures, market coordination through price mechanisms and service contracts, and network coordination through trust relationships (jie).

3.2 Cybercriminal innovation access modes

Unlike legitimate business innovation frameworks that rely on formal partnerships, intellectual property protection, and market mechanisms, criminal innovation patterns operate in an environment characterized by the lack of legal protection, resource constraints and operational security needs:

- Voluntary Innovation: Traditional collaborative relationships where criminal actors willingly share knowledge and resources (sscr). The comprehensive forum collaboration patterns documented in dark web analysis show continuous exchange of vulnerabilities, exploits, and attack techniques through professional development networks (trustcom).

- Appropriative Innovation: Non-consensual acquisition of knowledge and capabilities through espionage, infrastructure hijacking, and tool theft. Turla’s systematic hijacking of Iranian APT34 infrastructure demonstrates sophisticated appropriative innovation, gaining access to both Iranian victims and operational intelligence while using existing infrastructure for false flag operations (cyr, recordedfuture).

- Hierarchical Innovation: When state or institutional backing provides resources, protection, and coordination for criminal innovation activities, creating capabilities that transcend individual organizational limitations. For example, APT41 model’s combines state-sponsored espionage and parallel financially-motivated cybercrime (googlecloud), Operation Olympic Games (Stuxnet) unprecedented resource coordination enabled the development of cybersabotage impossible for non-state actors (jss), or the Lazarus Group sustaining multi-domain operations spanning espionage, financial heists, and destructive campaigns (nccgroup).

- Commons Innovation: Leaked or publicly available criminal knowledge to develop new capabilities. The Zeus botnet source code leak created an extensive commons innovation ecosystem, enabling smaller criminal groups to access sophisticated tools while contributing improvements and variations back to the broader criminal community (ctc).

These patterns extend beyond traditional open innovation frameworks by accounting for the unique constraints and opportunities within illegal cyber ecosystems, where formal legal structures don’t apply and trust operates differently than in legitimate business environments (oup3).

4. Criminal Modeling

The relationship between organizational hierarchy and innovation performance in criminal networks exhibits unique characteristics that distinguish them from legitimate organizations.

4.1 Innovation ecosystem hierarchy in cybercrime

Interpreting Granstrand and Holgersson’s (2020) innovation ecosystem definition (technovation), we develop a three tiers hierarchy of criminal innovation ecosystems:

Tier 1: Pure Criminal Networks – They operate with limited collaboration, focusing primarily on internal capability development. These organizations exhibit traditional closed innovation characteristics, relying exclusively on internal resources and limiting external knowledge flows due to operational security concerns (jrss, sr, bjc).

Tier 2: Criminal Innovation Ecosystems – They demonstrate sophisticated multi-modal access to knowledge and resources. These organizations actively engage in voluntary collaboration through forums and affiliate programs, appropriative innovation through tool theft and infrastructure hijacking, and commons innovation through exploitation of leaked materials (globalcrime). The Conti ransomware operation exemplifies this tier with its corporate-like structure, systematic training programs, and professional affiliate management (flashpoint).

Tier 3: State-Criminal Hybrids – They benefit from full institutional support, combining criminal innovation capabilities with state-level resources and protection. The North Korean Lazarus Group represents this tier, operating under Reconnaissance General Bureau oversight while conducting dual-mission operations combining intelligence collection with revenue generation through sophisticated cybercrime (mitre).

Theoretical boundaries and limitations as well as empirical edge cases reveal that Open Innovation theory is insufficient for criminal contexts. This hierarchy encompasses criminal-specific multi-modal innovation patterns to explain innovation dynamics in such configurations.

4.2 Empirical evidence for innovation diffusion

Cybercriminal organizations operate as innovation ecosystems with categorizable collaboration patterns:

Crime-as-a-Service model are structured business models with clear hierarchies: first-level administrators and experts, second-level intermediaries and vendors, and third-level operational personnel like money mules. This specialization enables efficient knowledge transfer and capability development across organizational boundaries (bcs).

Network structure analysis using Dutch Police intelligence data shows that criminal networks exhibit predictable structural features including efficiency-security trade-offs, with coordinators occupying strategic hub positions. These networks balance between redundancy for trustworthy replacements and non-redundancy for operational security (sr2).

Cross-group tool adoption provides evidence of technology transfer between criminal organizations. The widespread adoption of Cobalt Strike across multiple APT groups, sharing of Crime-as-a-Service platforms, and rapid spread of new attack techniques demonstrate effective knowledge diffusion mechanisms (proofpoint, microsoft).

Dutch police intelligence supports how these cybercriminal ecosystems systematically balance efficiency-security trade-offs while maintaining coordinator-hub positions that enable rapid knowledge transfer and operational continuity. The 2019-2020 161% increase in leaked Cobalt Strike usage across diverse threat actors and the proliferation of shared criminal platforms show systemic technology diffusion and collaborative capability development across organizational boundaries.

4.3 Organizational hierarchy and innovation performance

Research by Skrastins and Vig (2019) shows that hierarchical structures can block information flow in conventional organizations (rfs), but criminal networks demonstrate different patterns due to their operational requirements.

The forum-based collaboration patterns documented in cybercriminal communities show how horizontal knowledge sharing creates innovation opportunities that would be impossible in traditional hierarchical structures. Flat network structures then enable better knowledge integration and rapid adaptation to new opportunities.

Despite the tension between security requirements and innovation needs, criminal groups address those unique organizational challenges through hybrid governance approaches combining centralized control with decentralized innovation. As hierarchical control mechanisms provide necessary operational security while limiting innovation potential, cybercriminals need to master this equilibrium to stay alive: evade dismanteled while avoided criminal obsolescence.

Cybercriminal organizations operate as dynamic networks where each node is both a threat and an innovation partner, enabling rapid, secure diffusion of tools and tactics. To figth them, we must confront these agile, evolving ecosystems on their own adaptive terms.

5. Cases Analysis of APT Multi-Modal Innovation

5.1 Lazarus’ Operation Blockbuster multi-modal analysis

Operation Blockbuster represents one of the most comprehensively documented example of criminal innovation ecosystem analysis, revealing sophisticated multi-modal innovation patterns across a six-year operational period. The coalition investigation led by Novetta in partnership with Kaspersky Lab, AlienVault, and Symantec identified over 45 malware families attributed to the North Korean Lazarus Group, providing unprecedented insight into state-criminal hybrid innovation processes (securelist, novetta, talos).

Technical Innovation Patterns shows knowledge integration across multiple domains. The consistent technical signatures across malware families (misspelled user-agent strings, file deletion procedures, shared hardcoded passwords) strongly suggest centralized development practices with distributed deployment capabilities (threatpost).

The investigations reveal collaborative innovation evidence appears in the investigation methodology itself, where multiple private security firms shared intelligence to combat a single threat actor. This defensive collaboration mirrors the offensive collaboration patterns exhibited by the Lazarus Group, suggesting that innovation ecosystem principles apply to both criminal and defensive contexts.

Attribution Complexity resulting from tool sharing, false flag operations and fourth-party collection demonstrates the challenges created by criminal innovation ecosystems (cyr). The group’s operational security, including hardcoded sandbox hostnames and blurred timezone-based activity patterns, shows how innovation in criminal contexts extends beyond technical capabilities to include counter-intelligence and defensive measures.

5.2 State-Criminal nexus innovation patterns

Accross vendors’ threat intelligence APT litterature we can identify three primary models for state-criminal hybrid innovation ecosystems:

The north korean model : integration

Integrating criminal activities directly into intelligence operations through the Reconnaissance General Bureau, creates dual-mission capabilities that combine espionage with revenue generation (“slush fund”). The estimated 60% in cryptocurrency theft attributed to North Korean groups demonstrates how state backing enables sustained innovation investment (theindependant).

The russian federation model : competition

This model generates rapid capability development through institutional competition. Multiple agency relationships (FSB, GRU, and SVR connections) create competitive innovation environments where different state agencies sponsor parallel criminal innovation efforts (usni, uscongress).

The chinese Model : delegation

MSS-affiliated groups like APT31 and APT40 create contractor relationships that blur state-criminal boundaries (cisa). The indictment of seven APT31 individuals demonstrates how state sponsorship enables long-term innovation programs with sophisticated operational security (usjustice).

These three models collectively highligth that state-criminal hybrid innovation ecosystems have become essential components of modern geopolitical competition. This enable states to circumvent traditional deterrence mechanisms while accelerating cyber capability development through access to global criminal talent pools. State-criminal nexus transform cybercrime from a criminal enterprise into instruments of statecraft that challenges conventional notions of sovereignty and accountability in international relations.

5.3 Cross-group technology transfer

Technology transfer between criminal groups provides the strongest empirical evidence for Open Innovation patterns in criminal contexts, revealing three main transfer mechanisms:

Infrastructure Sharing enables resource optimization while reducing individual organization costs. The widespread use of bulletproof hosting services, shared anonymization networks, and common command-and-control infrastructure demonstrates resource pooling that mirrors traditional innovation ecosystem behavior (trendmicro, cisa2, sr3).

Tool Proliferation occurs through both voluntary sharing and appropriative acquisition. The documented cases of Turla’s hijacking of Iranian APT34 tools, Chinese APT groups adopting Russian techniques, and cybercriminal tools being adopted by nation-state actors show systematic knowledge transfer patterns (bankinfosec).

Methodology Transfer involves the rapid spread of new attack techniques across criminal networks. The evolution from simple DDoS attacks to sophisticated destructive malware demonstrates how criminal organizations systematically improve their capabilities through knowledge sharing and collaborative development (securelist2, cikm, barracuda).

Cybercrime evolved from isolated actors to a collaborative ecosystem where methodology transfer enables rapid dissemination of sophisticated attack techniques across criminal networks worldwide.

6. Edge Cases

Edge cases like Turla and APT41 illustrate how state-sponsored cyber threat actors operate according to Open Innovation principles: they do not rely solely on internal development but actively seek, acquire, and integrate external resources and capabilities. By hijacking infrastructure or tapping into state support, these actors highligth a predatory model where innovation stems from appropriation and reuse rather than isolated invention. This pattern underscores how openness to external inputs shapes the evolution of sophisticated cyber operations.

6.1 Appropriative Innovation: The Turla Case Study

Turla’s infrastructure hijacking operations represent the most sophisticated documented example of appropriative innovation in criminal cybersecurity organizations. The group’s systematic scanning for Iranian APT34 web shells across 35+ countries and successful hijacking of TwoFace ASPX web shells demonstrates how criminal organizations can acquire capabilities through hostile takeover rather than voluntary collaboration (recordedfuture).

Technical Analysis reveals sophisticated operational capabilities including the Mosquito backdoor’s multi-component architecture, Blum Blum Shub encryption with hardcoded modulus, and HTTP/HTTPS command-and-control communication using compromised WordPress sites. These capabilities demonstrate how appropriative innovation can lead to advanced technical development.

The implications of appropriative innovation include the creation of false flag opportunities, access to foreign intelligence targets, and the development of deception capabilities that complicate attribution efforts. This mode of innovation enables criminal organizations to access capabilities they could not develop internally while maintaining operational security.

6.2 Hierarchical Innovation: State-Criminal Resource Integration

The APT41 case study demonstrates how hierarchical innovation enables criminal organizations to access state-level resources while maintaining operational flexibility. The group’s ability to conduct simultaneous state-sponsored espionage operations and financially-motivated cybercrime using the same infrastructure represents sophisticated resource integration (googlecloud).

Resource utilization covers access to advanced threat tools, strong operational security practices, and sustained investment in developing new capabilities. The group’s $20 million COVID relief fraud alongside traditional espionage activities shows how state backing enables diversified innovation portfolios (nbcnews).

The convergence of state and criminal capabilities enables threat actors to innovate faster and operate with greater flexibility. Criminal networks benefit from state-grade resources and expertise without sacrificing freedom of action.

7. Threat Intel Application: Collaboration Pattern Analysis

Focus on criminal actors you already track confidently. Instead of mapping entire ecosystems, identify when your known threats start exhibiting new behaviors or capabilities. Ask yourself: “Where did this new technique come from?” and “Who else might adopt it next?”

Start small, think relationships, and use what you have

Work with existing intelligence feeds rather than chasing perfect forum access. Monitor for shared infrastructure through passive DNS, similar code patterns in malware samples, and timing correlations between campaigns. When three unrelated groups suddenly use the same new technique within 60 days, there’s likely a coordinator relationship worth investigating.

Track behavior changes, not static relationships

Criminal coordinators reveal themselves through influence patterns. When someone’s operational security advice gets implemented across multiple groups, or their technical preferences spread through a network, you’ve found coordination. Look for behavioral synchronization rather than direct communication evidence.

Make predictions you can validate

Focus on observable outcomes: “If Group A adopted this technique from a coordinator, Groups B and C should implement it within 90 days.” Track these predictions systematically. When you’re wrong, investigate why: criminal networks evolve faster than our models suggest.

Accept partial success

You won’t map entire criminal ecosystems, but you can identify influence relationships between 2-3 actors you monitor closely. Even limited coordination insights provide strategic value for resource allocation and threat prioritization.

Build incrementally

Start with one confirmed criminal relationship and expand gradually. Rushing to map complex networks leads to false conclusions and wasted effort. Criminal coordination analysis works best as a long-term intelligence discipline, not a quick-win tactical approach.

8. Conclusion

The distinction between APT and cybercrime proves less significant for Open Innovation Theory application than organizational sophistication level. Both criminal types exhibit similar collaboration patterns, knowledge sharing mechanisms, and innovation adoption strategies when operating at equivalent organizational complexity levels.

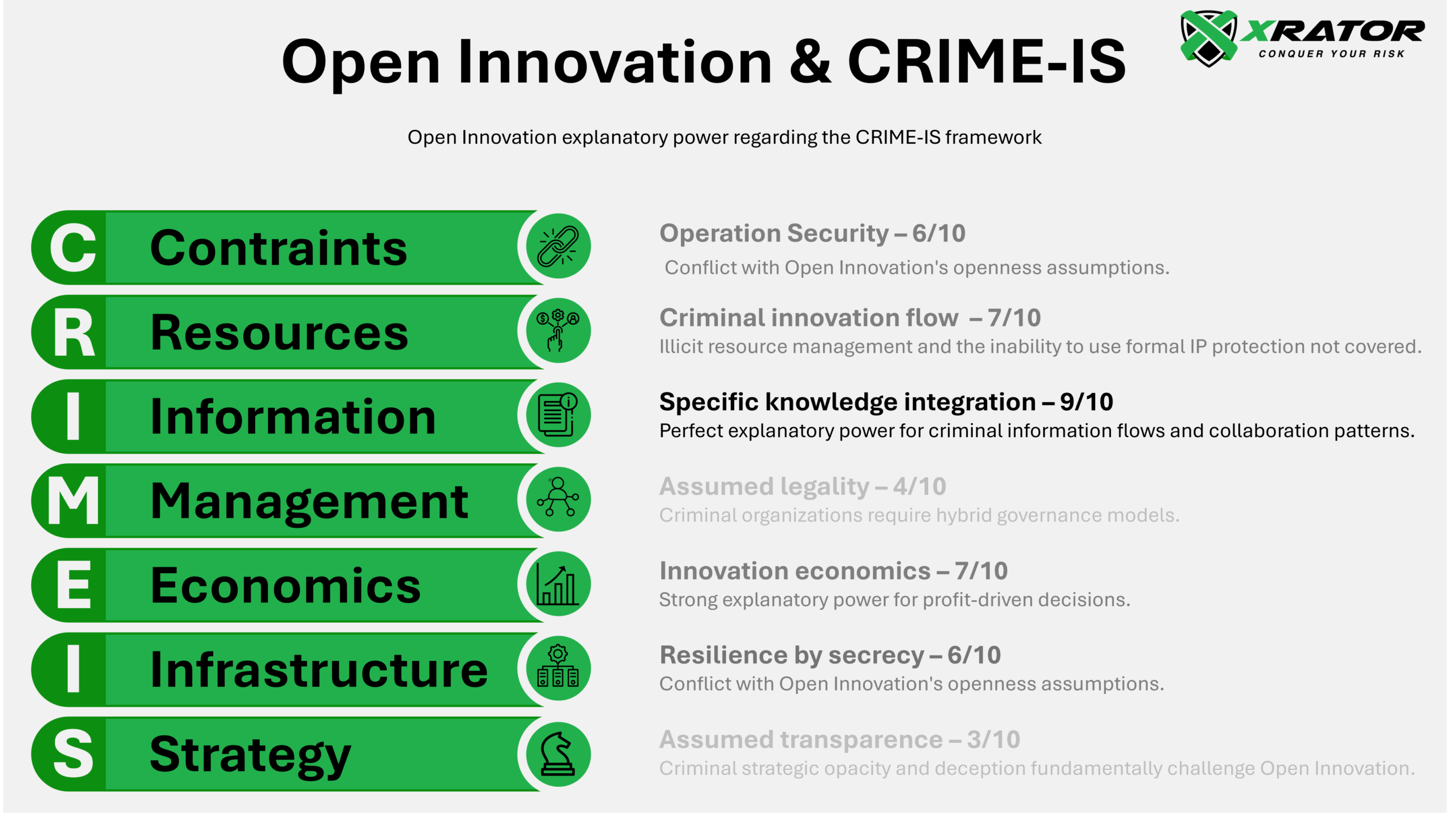

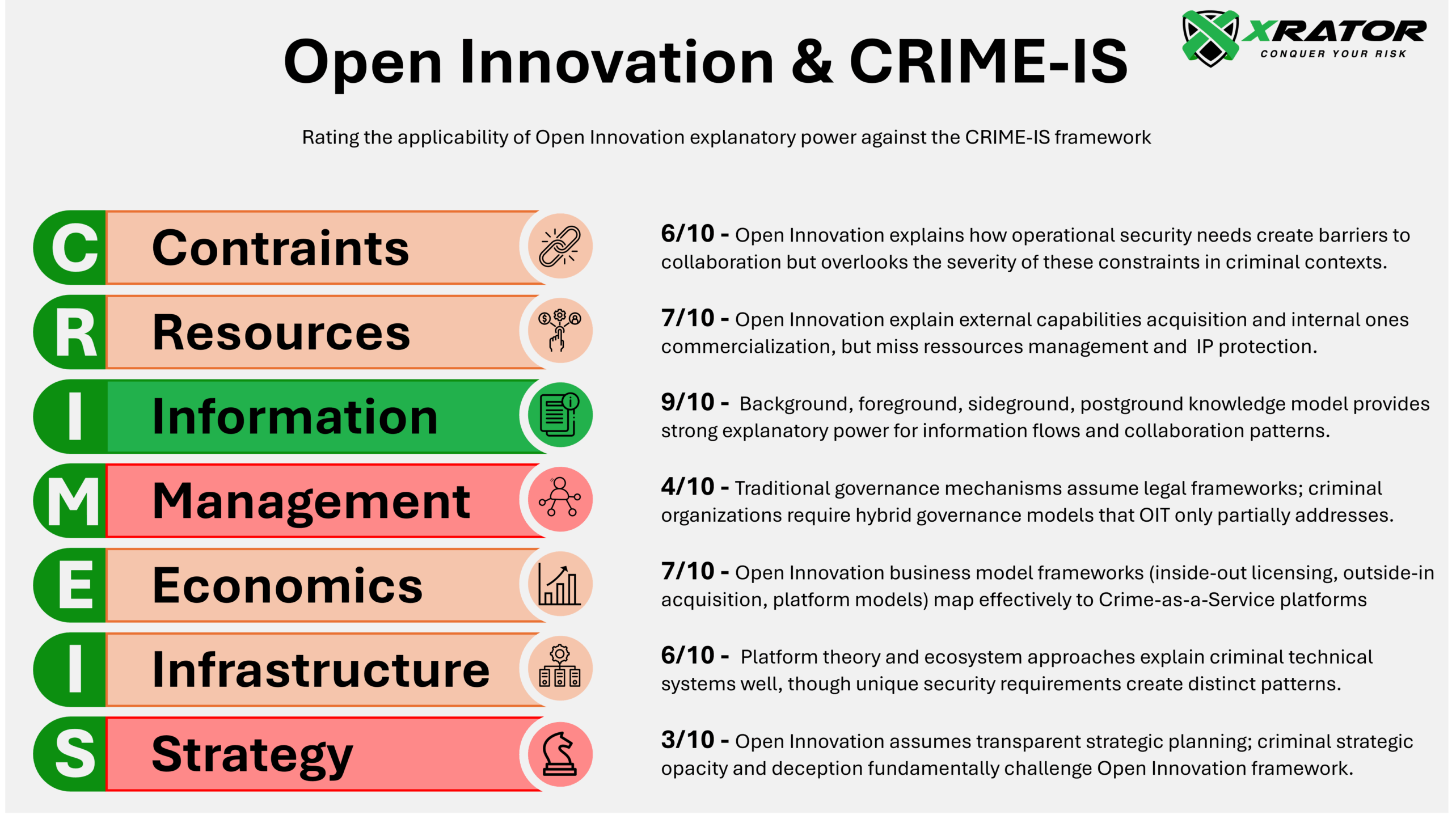

The transposition of Open Innovation Theory to criminal organizations through the CRIME-IS framework reveals a nuanced but largely successful theoretical application :

The framework demonstrates strongest explanatory power in:

- Information flows (9/10), where the four-type knowledge integration model perfectly captures criminal collaboration dynamics

- Resources (7/10), where inside-out/outside-in/coupled processes explain criminal capability acquisition and commercialization patterns

- Economics (7/10), where Open Innovation business model frameworks map effectively to Crime-as-a-Service platforms

Moderate success appears in Constraints (6/10) and Infrastructure (6/10), where Open Innovation’s openness assumptions conflict with criminal security requirements, creating recognizable but fundamentally different patterns.

The framework struggles most with Management (4/10) and Strategy (3/10), reflecting Open Innovation Theory’s core assumption of voluntary, legally-mediated collaboration that simply doesn’t exist in criminal contexts.

Regarding the four-dimensional transposition model, this limitation manifests most clearly in the Human dimension where trust mechanisms and behavioral motivations operate under fundamentally different constraints than legitimate organizations. However, the five-level taxonomy analysis reveals that this limitation diminishes as organizational sophistication increases.

| Threat Taxonomy | Cybercrime | APT | Explanation |

| Level 1 Individual actors | 2/10 | 1/10 | No organizational boundaries for Open Innovation knowledge flows |

| Level 2 Small groups | 5/10 | 4/10 | Limited outside-in/inside-out processes; minimal coupled innovation |

| Level 3 Formal org. | 7/10 | 6/10 | Clear three-process patterns emerge; systematic knowledge integration |

| Level 4 Ecosystems | 9/10 | 8/10 | Full Open Innovation applicability; complex multi-organization collaboration |

| Level 5 Service platforms | 9/10 | 5/10 | Perfect Open Innovation platform model fit for cybercrime; less applicable to mission-driven APT operations |

The five-level taxonomy remains highly relevant because innovation capacity correlates directly with organizational sophistication rather than criminal motivation. This suggest that organizational structure use mission objectives as a determinant of innovation behavior.

The critical insight emerging from this analysis is that organizational sophistication level, not criminal motivation, determines Open Innovation Theory applicability. State-sponsored APT groups and profit-driven cybercrime organizations at equivalent sophistication levels exhibit nearly identical innovation ecosystem characteristics.

We conclude that in our context, the traditional APT/cybercrime distinction, while operationally useful, obscures the fundamental reality that criminal innovation operates according to organizational principles rather than criminological categories.